For example, many of them are really Henry Ford historians--"History is more or less bunk. It's tradition. We don't want tradition. We want to live in the present, and the only history that is worth a tinker's damn is the history that we make today." (Chicago Tribune, 1916). But some of them might be Arnold Schwarzenegger historians--"Ba Ba Ba BOOM. You're History." (The Terminator, 1984).

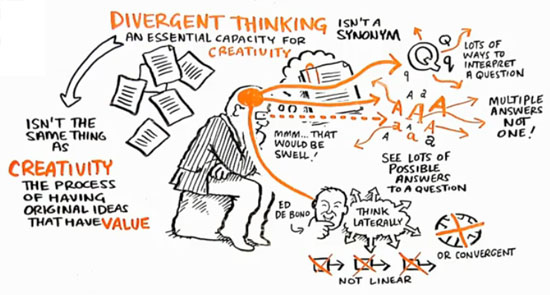

Another vital skill I have to remind myself to introduce is the idea of "divergent thinking." I wrote about this briefly in an earlier post where I paid the price and induced a frightened non-engagement in my class for a week because I forgot how crucial this skill is to creating an experience-based learning environment. So, what is "divergent thinking?"

The objective of divergent thinking is to generate a lot of ideas in a relatively short period if time. As two-time Nobel Prize winner Linus Pauling famously said, “To get good ideas is to get lots of ideas, and throw the bad ones away.”

Years ago there

was a study that tested “divergent thinking” on a group of people. These people were in kindergarten. The

percentage of people scoring at “genius level” for divergent thinking was ---

ready, 98%. When that group was tested

five years later that number was down to 32%.

When these children were fifteen years old, the number was down to

10%. By the time they were twenty-five,

the number was down to 2%. When I ask my students what they ascribe this downward trend to they are quick to say, "School." Regardless of whether they are right, it is kind of damning that they think this in the first place.

One of the major reasons we create environments that are not experience-based is because we are so focused on convergent thinking. We have a lot to cover, and we need every second to transmit that information to our students. In the past few years I make sure I have "shadowed" a student through their class day as an exercise to try and see the world from their point of view. What I find is the explicit or implicit goal of virtually every class is to converge down to a formula, a piece of information, a previously held interpretation. In short, the objective is to know something but the process is almost always a converging down on an answer, not on an opening up to an exploration. Divergent thinking is something that fosters the latter, and I always have to remind myself to include it as part or all of classes early in the year. And then I have to remember to keep doing it.

I thought I would practice a little divergent thinking myself on the topic of the "purpose of studying and doing history." There are a few rules in divergent thinking--avoid judging what you are thinking, try to be additive and play off what you just thought and be as playful as you can are vital. As Plato said, “What, then, is the right way of living? Life must be lived as play.”

So, here goes:

Some Reasons to Study and Do History:

1) George Santayana- “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it."

This seems to be the most common starting place for history teachers in staking a claim for the relevance of their discipline. However, I find that few historians actually subscribe to it. The "condemned" part seems both didactic and prescriptive. History certainly has to do with the past, but the past can't be repeated. At least that is what every historian I know thinks. This, of course, was the downfall of that non-historian, Jay Gatsby--"Can't repeat the past? Why, of course you can."

2) You can't repeat the past, but there are cycles and patterns that can help you identify where you came from.

Arthur Schlesinger was very big on this idea; he saw the identification of these cycles as leading to a more ideal society. For Schlesinger, the tension between pragmatism and idealism is part of the American character. It is important, however, that the identification of cycles is never helpful as a predictive mechanism. That is a fundamental difference between social scientists and historians. The former are trying to be predictive; the latter never are. Historians are wary of generalizations and dwell in particular settings, whereas social scientists are using particulars to achieve general theories and rules. Understanding the difference between social sciences and history is crucial and often muddled in a way that confuses students.

3) Maybe the past cycles, or maybe it provides models and analogies for the present and the future.

Richard Neustadt was a big proponent of this. Much of this argument sees the past as a powerful analytic tool for making policy decisions. It uses case studies to examine whether something happening now is analogous to something that happened in the past. For historians though, models are like lenses on a camera, they bring some things into focus while blurring other things. It is a trade-off, you see some things more clearly but you miss other things completely when you use any model or analogy.

4) Perhaps the way to see the past most clearly is to see it through the lens of myth?

Rollo May wrote a good deal about this. Myths, in this view, are not falsehoods, they are stories that are either living or dead. The way to understand the unconscious of another world is to understand its myths. As May wrote, "A myth is a way of making sense in a senseless world. Myths are narrative patterns that give significance to our existence [...] myths are our way of finding meaning and significance. Myths are like the beams in a house; not exposed to outside view, they are the structure which holds the house together so people can live in it." Myths tell us what we have internalized in our unconscious in ways that we are unaware of--another version of the DKDK zone.

(Divergent

thinking should not be confused with brainstorming, by the way,

although they are related. Brainstorming is a technique that encourages

divergent thinking. Brainstorming is just one of many possible ways to

produce divergent thinking, however.) - See more at:

http://www.creativitypost.com/psychology/most_of_what_you_know_about_divergent_thinking_is_wrong#sthash.EPeBaKCS.

5) If myths aren’t true or false but, rather, living or dead, then we gain self-knowledge by understanding

change over time in the mythic as well as the “historical” sense. The unveiling of underlying collective, cultural myths gives one a greater control over one’s life in the present. In other words, an understanding of one's deeply held myths is essential to both national and individual mental health.

Here is an experiment I have been running for thirty years since I was reading May's work. What book has EVERY American read or had read to them? My findings have been that I can say four words to you and you will all give the same answer. Ready? Here are the words-- "I think I can."

Answer--The Little Engine That Could. Every year, the students who are "American" howl with delight that they all shout out the same thing. The "non-American" students just look quizzically at that behavior. The reason is that the "myth" of that story, and its multiple lessons on persistent striving and being the underdog, is so deeply internalized in our culture that it tells us, as a country, who we are. Interestingly, from an historian's point of view, it may be one of the myths most in jeopardy of dying right now.

6) Mark Twain looked at the past in a kind of poetic way--"The past does not repeat itself, but it does rhyme."

What I am realizing in this divergent thinking exercise is that studying and doing history provides a context for our lives. It reminds me of the philosophers--I remember reading Ludwig Wittgenstein in grad school--who believe that the origin of meaning is really in context. In other words, meaning comes primarily when we are able to put something--a word, an event in our lives--in context. Without context, you have no meaning, only action. We need history in order to provide meaning for our lives. History is like the landscape of a scene you are looking at; you need that landscape to provide context that will tell you where you are. Perhaps history is to one's life what perspective is to a painter. I confess, however, that there are times that I think I am teaching history to people who are the least historical people (teenagers) in the least historical country (America) in the world.

7) And, of course, William Faulkner saw the past as always with us when he wrote, "The past isn't dead; it isn't even past."

I think this is true, and it is most obviously seen in the idea of history as being actually similar to memoir--something I talked about in an earlier post. But Joan Didion is perhaps the person who resonates most deeply on this topic, and provides a nice closure to this first set of divergent thinking posts. She writes in "On Keeping a Notebook," “I think we are well advised to keep on nodding terms with the people we used to be, whether we find them attractive company or not. Otherwise they turn up unannounced and surprise us, come hammering on the mind's door at 4 a.m. of a bad night and demand to know who deserted them, who betrayed them, who is going to make amends.”

Put Faulkner and Didion together and you end up with a poignant plea for history as a necessary signpost to self-knowledge and deeply understanding who one is as a person. But that understanding only comes when something means something. Studying and doing history provides the necessary context that allows that kind of deep meaning to emerge.

What this little piece of divergent thinking has shown me is the power of connection, and the way in which you create idea through that act of connecting. Next time, I will play off some of these ideas to explore reasons to study history based on the role of narrative, the relationship of stories to intelligence, and empathy.

Once, in a past that may or may not pass for history, you and I rode around on a golf cart during camp evenings and tried to figure various meanings of life. Now, as I approach another year of teaching, I take the caution at the head of this post to heart - whatever I've figured out about "life" needs to be shelved much of the time as I listen to my students' questions and speculations about what they've figured out or where they've gotten stuck. Here's a quotation from RW Emerson that I reread each year, and that, this year, goes at the head of the course about Henry Thoreau and assorted kindred spirits that I'm about to teach. Like most of us, Emerson wanted an original life, not one shaped by received wisdom. And so he asked this:

ReplyDelete"Why should not we also enjoy an original relation to the universe?" RW Emerson in the essay Nature

sandy...just back from imitating john muir in the sierra's...and off to the southwest when the government goes back to work...emerson's words echo muir in some ways....thanks for commenting.....i am working right now on the idea of "things we feel in our bodies" particularly being startled....which i believe did happen at hobart in the golf cart and certainly did for me in kings canyon last month....hope to see you soon

ReplyDeletekeep the faith

david