When my students returned from holiday break there was a palpable pall that seemed to have settled over all of them. As one student put it, "You should just think of it as like the beginning of the year; we have to learn everything all over again." But I wasn't asking them to remember anything, I just wanted them to be playful, to make some guesses about a text we were exploring. Essentially, I wanted them to play the "inference game" and make as many predictions as they could about a text; but they weren't having it. I saw it as a kind of refresher that took a basic skill--generating inferences through divergent thinking--and did it in a non-threatening way.

After a fairly extended discussion where I tried to coax out an explanation for why they were having none of this "so-called game" one student said something that went to the heart of the matter.

"Well, we aren't going to be playful and make guesses because we know what the next question is going to be," someone stated.

"What's that?" I asked.

"'Where did you get that idea from? Where do you see it in the text?' Show me. Right?" she replied.

"Really? Is that what will happen?" I wondered aloud.

"We aren't going to be playful if we know the next question is going to potentially make us feel stupid and vulnerable. We are passive because we can see what's coming down the road, and it's going to hurt. Don't take it personally--it happens in every class," the student added in a consoling manner.

I wanted them to be playful and practice making guesses based on inferences. But they had rightly realized that the structure of the game was actually a trap -- that if they played it they would then have to justify their imaginings with a reference to the text. I saw it as an imagination game; they saw it as offer proof for what you think. In other words, there would be a competing commitment of textual verification adding on to this playing with inferences. That is what had happened, I had unwittingly set up two opposing ideas that were in competition. Two ideas that I deeply loved--making inferential guesses on the one hand, and being tight to the text and exploring it in minute detail on the other--were running headlong into each other. My class had become a train wreck, and I was responsible. My intention of having the kids playfully work with their imaginings to get close to the text had the unintended implication of making them feel vulnerable.

I thought back to every sheet that I had seen passed out in the school about the way you could contribute to seminar discussions. They were full of roles that were all about referencing the text; nowhere was there a role like, "makes helpful, playful, intuitive inferences and predictions about a text." Making guesses without any analytic evidence was always a bad idea in this arena; they were right. My eyes flitted up to a ring of signs above the whiteboard suggesting these roles that another teacher had put there as reminders. I was literally surrounded by the evidence.

Bob Kegan, from the Harvard Education School, has written a lot about why people are hesitant to be adventuresome and try new things, why they don't change. One of the reasons he cites is the idea of the "big assumption." Kegan would describe this as the deeply rooted beliefs about ourselves and the world in which we live. They act kind of like the ego would in Freudian theory--they are a necessary protective device used to keep order. Part of getting people to change, Kegan would say, is getting them to surface and identify what might be competing commitments and act on them. If you can't be brave enough to self-implicate and do that, then you just thrash about and can never affect change in yourself or your surroundings.

We often have big commitments that are all about grand ideas, and any school's mission statement is filled with them: "encouraging creative habits of mind that induce a passion for life-long learning." And then we have competing commitments to concepts like grades that research has shown to be counter-productive to precisely those values cited in the mission statement. Those competing commitments produce a kind of humorous mixed metaphor at their best and a kind of schizophrenic anxiety at their worst.

As a huge fan of Kegan's, one of the things I have learned is that when my classes are not going well it is often the case that there is a "big assumption" that my students hold that is not allowing them to grow. However, often times I am the cause of their doldrums, their anxiety, their feeling vulnerable and unsafe. When I can unearth the competing commitment, we can then get back to learning.

Here is an example of how competing commitments work in non-academic settings. After all, as John Dewey said, "Education is not about preparation for life; it is life.":

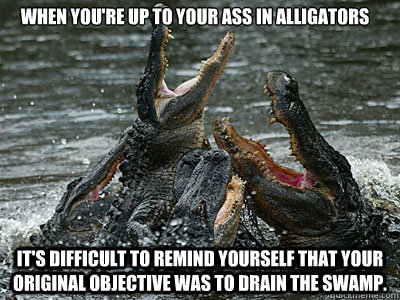

When I was a teenager, my father would post a note (a copy of which is at the head of this blog post) on the refrigerator as a way of communicating to me--first thing in the morning--how I might have "not thought things through as carefully as you might have." The sign said simply, "When you are up to your ass in alligators, it is difficult to remember that your original intention was to drain the swamp."

I clearly remember being a bit confused and flummoxed when I saw the sign for the first time. I had to read it a couple of times to understand and make the application. I got used to it (I saw it a fair amount some years), but it has come to be a kind of mantra for me when I try to explain the concept of unintended implications.

So, I was up to my ass in alligators again. I think what I have found is that even when you have the best of intentions, you better make sure that swamp doesn't have competing commitments in it.

I had created competing commitments in my class and couldn't see that I was reaping what I had sown--with all the best intentions. I think this is why I have only a little patience with teachers complaining about their students; I want to make sure they have gone through the necessary self-implication.

I saw, in my mind's eye, my father putting the sign on the refrigerator door again. I wonder what it would be like if this were part of a school's mission statement? It is certainly part of the one for my classroom.