I love the cornucopia of ideas that come from these authors, and I love reading books that affirm what we have been practicing at CITYterm for the past decade or so. Every time I read these books and then I look at the skills assessment sheet that we design our course of study from, I feel encouraged that we are on the right path. My problem with all of these calls for empathy is that there rarely seems to be a hands-on look at HOW one practices empathy. What is the precise plan of action? What does one do in class to make this happen? Or, looking at the problem from a reverse angle --what gets in the way of practicing empathy? What makes it difficult to do?

The way empathy gets talked about in these books, however, reminds me more of a coach I was listening to at a basketball camp one summer who was explaining how to run a fast break. He started his lengthy exposition with these words, "First, assume a rebound..." But, it seems to me, we should spend some time learning how to rebound before we start running fast breaks. If you don't have the skill of getting the ball, it doesn't help to affirm how valuable it is to run a fast break offense.

Or, as my economics professor in college said when asked about the limitations of economists' thought processes in approaching problems replied, "Well, a lot of us (economists) are like a starving sailor stranded on a desert island with nothing to eat, but a whole case of canned tuna fish has washed up next to us. So, we think, 'How shall we solve this problem?' Economists are people who are prone to approach this problem by saying something like, 'First, assume a can opener."

In the next few posts, I would like to explore what I think are some of the precursors for the practice of empathy. This particular post will be about one of the antecedents that we can't assume to be there--like the rebound in the basketball game or the can opener on the desert island. In fact, we may live in a culture that is hostile to it.

The very first concept that is important to introduce when you are trying to facilitate someone becoming an experience-based learner is the DKDK zone--what this entire blog is named for. Being able to get yourself into the DKDK zone sets in motion a entire series of cognitive skills that make the learning transformative. When I first started practicing getting students into the confusion and disequilibrium that is the inherent in the DKDK zone, I began to notice that one major obstacle kept short-circuiting the spark that needs to be part of the process. That obstacle was my student's deeply held fear of ambiguity.

But look at other words constructed using the Latin "ambi" or the Greek "amphi." People who are "ambidextrous are not "unclear" about whether they are right or left handed; they are both. (Though, as a side note, "dextrous" means right-handed, so the bias and prejudice against left-handed people is certainly contained in the word.) And as my friend Christopher pointed out to me this week at the Teaching for Experience teacher workshop, people who are "ambivalent" have simultaneous and contradictory attitudes and feelings, they are not inconclusive, irresolute, or unsure. Amphibians can live on both land and in the water; they are not unsure about where to live! And, an amphitheater is one where you can see the stage from multiple angles.

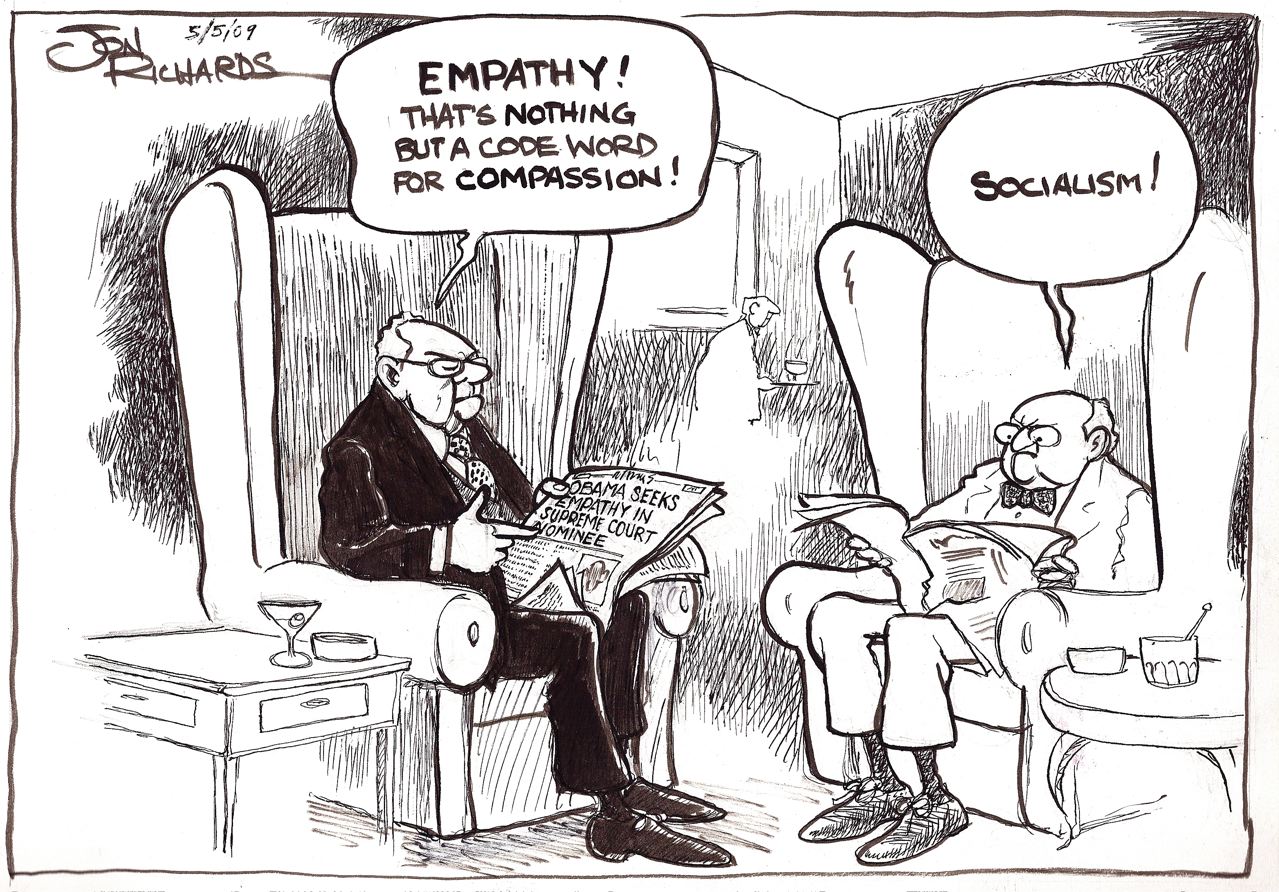

My point is this, the society we live in is fearful of ambiguity and will do anything to resolve the dilemma of something having multiple meanings. If you keep digging in the dictionary, it is only after you get down to some secondary definitions that you come to "capability of having two meanings" (which emerges in the 15th century). Dichotomies reign supreme, but so often in an "either/or" sense and not in a "both/and" sense. Look at the contemporary political and social world and notice how much we avoid complexity in exchange for oversimplification. As H. L. Mencken said, "For every complex problem, there is an answer that is simple, direct and wrong."

And because my students are being culturally trained to fear ambiguity, they are at a huge disadvantage in trying to be empathetic. It is a similar phenomenon to when I discovered that some of my students do not "wonder" at all during the course of a day. It makes "wondering and wandering" a hard skill to practice. In a similar manner, many of my students spend most of their day trying to avoid ambiguity every time they come across it.

In order to be good at empathy, you have be well practiced in contradiction and multiplicity. In short, you have to understand ambiguity and embrace it. This is what I explored in an earlier post on Walt Whitman and his capacity for empathy on a cosmic scale. As Whitman warned us in "Song of Myself, "Do I contradict myself?/Very well then I contradict myself,/ (I am large, I contain multitudes.)" Any teacher trying to move their students towards empathy would do well to have a sophisticated theory of what will be the major difficulties on that journey. One of the major difficulties will be embracing ambiguity and having a clear idea idea of where in each lesson this possibility will arise.

Interestingly, a new study recently released by the University of Toronto addresses this precise problem. Part of the study reads, "Are you uncomfortable with ambiguity? It’s a common condition, but a highly problematic one. The compulsion to quell that unease can inspire snap judgments, rigid thinking, and bad decision-making. Fortunately, new research suggests a simple antidote for this affliction: read more literary fiction. The study goes on to talk about how reading fiction in certain ways may increase people's capacity for "disorder and uncertainty" and increase "sophisticated thinking and greater creativity." The reader, they conclude, "can simulate the thinking styles of people he or she might personally dislike. One can think along and even feel with Humbert Humbert in Lolita, no matter how offensive one finds this character."

And, in one of those "the world speaks to you" moments that happen in experience-based learning, a friend sent me Joss Wheldon's recent commencement address at Wesleyan University. Toward the end Wheldon's speculates,

"Our culture] is not long on contradiction or ambiguity. … It likes things to be simple, it likes things to be pigeonholed—good or bad, black or white, blue or red. And we’re not that. We’re more interesting than that. And the way that we go into the world understanding is to have these contradictions in ourselves and see them in other people and not judge them for it. To know that, in a world where debate has kind of fallen away and given way to shouting and bullying, that the best thing is not just the idea of honest debate, the best thing is losing the debate, because it means that you learn something and you changed your position. The only way really to understand your position and its worth is to understand the opposite...This connection is part of contradiction. It is the tension I was talking about. This tension isn’t about two opposite points, it’s about the line in between them, and it’s being stretched by them. We need to acknowledge and honor that tension, and the connection that that tension is a part of. Our connection not just to the people we love, but to everybody, including people we can’t stand and wish weren’t around. The connection we have is part of what defines us on such a basic level."

As is often the case in experience-based learning, it is the quality of our relationship (what Wheldon calls the "connection") that is the determining feature of what we learn. How can we learn to endure, even embrace, that tension? If we do that, I believe, we increase our capacity for empathy.